|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

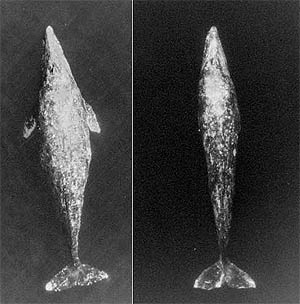

Gray whales migrate south (and north)  A gray whale blowing as it swims along the sea surface. (Source: Steven Swartz / NOAA/NMFS) Whale watching in January is always an adventure. It's best to pick one of the calm days between storms, when whale spouts are relatively easy to spot. Make your way to an exposed cliff along the open coast, which has a wide view of the sea. If you watch long enough, you may be rewarded with the sight of gray-whale spouts on the horizon. By January, most gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) are heading south from their feeding grounds in the Bering Sea toward their calving areas along the coast of Baja California. The largest number of southward-migrating gray whales typically passes through Central Coast waters in mid January. By late February, you may also see a few gray whales heading north as well.  Aerial photos of near-term pregnant (left) and normal (right) gray whales. (Source: NOAA/SWFSC) Many of these gray whales are in a hurry--they are pregnant females who want to reach the warm lagoons of Baja California before they give birth. Each year a few of them give birth while "on the road," so you may occasionally see baby whales at this time of year as well. However, these young whales have a hard time nursing enough to put on weight and build up their strength, while keeping up with their mothers. Even more threatening to the baby gray whales are packs of transient orcas ("killer whales") which sometimes follow the migrating females. When they detect a weak baby whale, they close in for the kill. Despite the mother's best efforts to shield her baby, the orcas are sometimes able to separate the mother and calf. In this case, the calf becomes easy prey, and provides a floating feast for orcas and sharks. Note: Gray whales mate in their northern feeding areas just as they are beginning their southward migration. Females come into estrus during a three-week period from late November to early December. If fertilized, they will give birth a little more than a year later. Winter-resident dolphins feed near shore If you get out on a boat in Monterey Bay during January, you may see pods of winter-resident dolphins following whatever schools of anchovies or squid may be present in the bay. These winter residents include Pacific white-sided dolphins, Risso's dolphins, and northern right whale dolphins. Juvenile sea lions arrive just as adult sea lions head south In February or March, adult California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) begin to leave the Central and Northern California Coast and head south to their breeding areas on the Channel Islands and along the coast of Baja California . Sometimes groups of these adult males will stop briefly along the Central Coast to feed, but like the orcas, they don't stay long. You may also see rafts of young and juvenile sea lions start to appear along the Central Coast at this time of year. These groups often include many young pups as well as a few older juveniles who guard the pack and keep the youngsters in line. We'll look at these groups of rowdy youngsters in greater detail in April. Elephant seals give birth and then mate  Elephant seal pup nursing. (Source: Brandon Southall, NMFS/NOAA) January is an exciting time to visit the elephant-seal breeding colonies along the Central Coast. It's a little like a rerun of that old TV show, “Here Come the Brides.” For the last month or so, the giant male elephant seals have been fighting for breeding territories. But these territories have been pretty much unoccupied. Finally, in late December or early January, the female elephant seals begin to arrive at the breeding grounds. These females have been swimming around the northeastern Pacific since April of the previous year, fattening up on deep-water fish and squid. Ten to twelve feet long, and weighing 1,200 to 2,000 pounds, the female elephant seals are nonetheless dwarfed by the males, which may way twice as much. Many of the newly arrived females are pregnant, having been inseminated the previous winter. Less than a week after arriving, each of these females will give birth to a single pup. After giving birth, the female elephant seal will nurse her pup almost continuously for 25 to 28 days, pumping an astounding amount of high-fat, protein-rich milk into the little creature's body. By the time she is done, the pup will look like a six-foot-long gray, speckled sausage. Elephant-seal researchers call the pups who have finished nursing "weaners," but from their appearance, they might just as well be called "weiners." The female elephant seals are so dedicated to the birthing and nursing process that they do not eat at all after coming ashore. While their babies triple in weight, the female seals may lose as much as one third of their body weight while nursing their young.  Elephant seals mating. (Source: Denise Kocek / NOAA) In February, soon after the babies are weaned, the adult females become receptive to mating. At this point, the toughest male elephant seals, winners of December's battles for territory, mate with several females in their harems. According to one research paper, "Copulatory activity peaks on February 14, St. Valentines Day." Note: Despite all the male posturing and guarding of harems, the dominant males don't do all the mating; losing males sometimes sneak in to mate with females in another male's harem. After they finish mating, the male elephant seals leave to go get a bite to eat. But they don't just head down to the corner convenience store--they swim thousands of miles away, to the Aleutian Islands and the Gulf of Alaska. White sharks leave the Central Coast Note: Obviously, white sharks aren't marine mammals, but I've included them here because they are so intimately linked with the sea lions, harbor seals, and especially the elephant seals that form the bulk of their prey. By January, many of the white sharks that have haunted the elephant seal breeding grounds since fall begin to leave the area. The male sharks leave first, typically between late November and early January. The females, however, stick around for another month or two, possibly because they are usually larger then the males, and require more food. Satellite tracking tags have shown that in February or March, these male and female white sharks congregate in an area about half way between Baja California and Hawaii. Scientists don't know exactly what they are doing out there, but its possible that they leave the elephant seal breeding grounds to do a little breeding of their own. Shortly afterward (in early spring), female white sharks apparently give birth to live young in the protected waters of the Southern California Bight (from Point Conception to the Mexican Border). However, pregnant females have never been seen in this area. Perhaps they come in toward shore, give birth, and then leave shortly afterwards. As they grow up in the warm, sheltered waters of Southern California, the young white sharks feed on smaller sharks and rays as well as California grunion (which is famous for spawning on Southern California beaches during spring and summer). As the young white sharks grow larger, they tend to migrate both northward toward Central California and southward along the coast of Baja California. At this point they begin to eat larger fish, and eventually expand their menu (and their jaws) to include harbor seals and California sea lions. Note: Since about 2015, juvenile white sharks have been appearing in larger numbers in protected parts of Monterey Bay, such as the Seacliff Beach area. This phenomenon may be due to episodic or long-term warming of water in the bay. Baby sea otters nurse on their mother's bellies  Sea otter pup sleeping in the kelp beds. (Source: (c) Kim Fulton-Bennett) With the kelp canopy thinned out, it becomes relatively easy to see the most obvious and charismatic animal in the kelp beds—the sea otters (Enhydra lutris). January and February are the best months to see female otters floating in the remains of the kelp beds with newborn babies on their stomachs. Although sea otters mate and give birth all year round, most mating occurs in late summer and most sea otter pups are born between November and March. By February you are likely see babies in a variety of ages and sizes. About the size of week-old kittens, newborn sea-otter pups are hard to see, even with binoculars. They can be very hard to see as they cuddle up on their mothers' stomachs. It's amazing that the mother and baby can stay together even as winter storms bring 10- to 20-foot waves that break out in the kelp beds. Note: It has always puzzled me that sea otters, which spend their whole lives floating just outside the surf zone, would give birth to helpless infants at the time of year when their habitat (the kelp beds) is at a minimum, and when they are at a risk of being exposed to 20-foot breaking waves. From an evolutionary perspective, there must be some reason for such behavior. My guess is the young otters are most likely to survive if they learn how to forage in spring, when food is relatively abundant and easy to capture (because the understory algae haven't grown in yet). One thing that helps the baby otters survive winter storms is their built-in "life vest" of thick, buoyant fur. This fur is so buoyant that the baby otters pop back up when submerged by a wave. However, this thick fur also prevents them from being able to dive beneath the surface. This means that the baby otters are completely dependent on their mothers for food until their regular fur grows in, when they are about two months old. To their credit, female otters do seek out relatively protected parts of the coast to give birth. Usually these are places where the kelp beds are thickest during the summer months and substantial patches of kelp remain throughout the winter months. Such areas include sheltered parts of the Monterey Peninsula and the rocky coastal areas between Capitola and Pleasure Point, and sometimes along West Cliff Drive in Santa Cruz.  Sea otter pup nursing. (Source: Mike Baird / Wikipedia commons) Unlike many marine mammals, female sea otters cannot give up eating while nursing their babies. Since they don't have blubber, they need to eat every day to generate body heat so that they don't freeze to death. When hunting a female otter typically wraps her pup in the kelp before diving for food nearby. Young pups sometimes becomes anxious if its mother is away too long or surfaces some distance away. In this case, the pup may issue a high-pitched, squeaking cry that can be heard even over the roar of the breaking waves. When the female otter surfaces, her pup may swim over to her to get a share of whatever she came up with. However, not until the pup is three or four months old will the pup begin to eat solid food. The young otter will continue to nurse for four to six months or more, growing rapidly on milk that is about one quarter fat. When nursing, young otters often lie head-to-tail on their mother's bellies, because the mother's nipples are on the lower part of her belly. Female otters also spend a great deal of time grooming their babies to keep their fur clean and waterproof. If the female otter feels seriously threatened, she will use her teeth to grab her pup by the loose skin of its neck and then dive with the baby in tow.  Sea otter mother and pup sleeping in the kelp beds. (Source: (c) Kim Fulton-Bennett) As January turns to February and the baby otters become more independent, you may see groups of mothers and pups floating together in areas where the kelp canopy has survived the winter relatively intact. They apparently set up a "baby-sitting clubs" that allow the females to get a little sleep while their youngsters swim around nearby. These informal social groups sometimes include one or more single otters who may be offspring from previous years. In the dense kelp beds off West Cliff Drive, I have seen such groups remain in the same patch of kelp for months at a time. Month-old otter pups are perhaps a third as long as their mother, and fit easily on her stomach to nurse or nap. By the time they are three or four months old, the pups may be getting too big to fit on their mothers' stomachs. But that doesn't stop them from trying. I have often seen female otters who could barely keep their heads above water while swimming with large pups on their bellies. |