|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

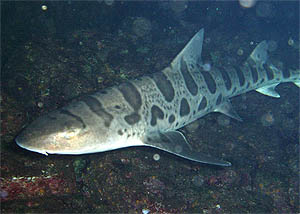

Overview Coastal estuaries in May are filled with warm water and living organisms of all sizes. Blooms of microscopic algae support copepods and microscopic larvae of estuarine animals, as well as hordes of small fish. Lush beds of eel grass and marsh vegetation provide both habitat and food for a myriad of crabs, shrimp, snails, and small fish. As this vegetation decays and is carried away by the currents, it provides food for animals living in burrows within the muddy bottom of the estuary. Many of the young fish hiding in the greening marsh-meadows in May were born in the slough during the winter or early spring. These include herring, anchovies, and staghorn sculpin. By May these fish have become juveniles and are almost ready to leave the nursery. At the same time as these young fish are getting ready to leave, adults of other species (including shiner perch, leopard sharks, and bat rays) are entering estuaries to give birth or feed. Their young will develop throughout the summer in these protected, food-rich environments. Many people know about the yearly return of the swallows to Capistrano, but few have heard of the yearly migration of elasmobranchs to Elkhorn Slough. In April or May hundreds of these cartilaginous bottom dwellers begin to arrive, gliding silently into the sinuous channels of the slough and up onto the shallow mud flats with the incoming tide. These summer visitors include leopard sharks, bat rays, and shovelnose guitarfish. The first two come to the slough to give birth. The last uses the slough as a critical feeding ground. Coastal wetlands grow warm and lush With the long, sunny days of May, the surface and shallow waters of coastal estuaries such as Elkhorn Slough often become quite warm during the daytime. However, in Elkhorn Slough and other estuaries that have a deep, permanent connection to ocean, the water more than a few inches below the surface remains cold throughout the spring, gradually warming to a yearly peak in July, and remaining warm through October (similar to the nearby ocean). Because rain and runoff events are relatively infrequent after April, the salinity of the water in ocean-connected coastal estuaries such as Elkhorn Slough is often similar to that of the nearby ocean. Estuaries that are blocked off from the ocean by a seasonal sandbar (such as river and stream mouths) are likely to become much warmer than the ocean in spring and summer. However, their temperature and salinity may vary greatly depending on the balance between streamflow, solar evaporation, and breaching of blocking sand bars, which may cause draining of the lagoon and/or inflow of ocean water at high tide. With abundant sunlight and relatively clear water, underwater plants such as eel grass and green algae such as Enteromorpha grow rapidly, sometimes choking shallow-water areas. Young fish and seafloor animals such as the green shore crab (Hemigrapsus oregonensis) hide out in these dense underwater thickets, eating the plant-life and smaller animals that share their habitat. The warm, turbid water in the shallow parts of coastal estuaries create ideal nursery areas for young fish. For one thing, the fish grow more quickly in warm water, and the faster they grow the more likely they are to survive. The abundant plants and microscopic algae in the estuaries grow quickly and decompose rapidly when they die, providing plenty of food for both small fishes and their prey. Finally the shallow, turbid water of the shallows may make it harder for larger predators to find small fish, or even get to them. Note: During periods of extreme high and low tides, both living and decaying plant material, as well as the shed exoskeletons of rapidly growing shrimps and crabs, are picked up by the currents and carried throughout the slough and even out to sea. This material provides food for herbivores, such as snails, scavengers such as crabs, and filter feeders such as worms and clams. Juvenile herring leave estuaries  Juvenile herring, about three months old. (Source: USGS) Among the fish in Central Coast estuaries in April and May are juvenile Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii. These herring originally hatched from eggs that were released in January or February, and drifted around as larvae during February and March. By late spring, they will have developed into juveniles and are busy feasting on the spring crop of copepods. Those juvenile herring lucky enough to avoid being eaten by flatfish and birds will leave the slough in May, swimming out to the kelp beds and coastal water, then eventually the open waters of Monterey Bay. Out in the ocean, the juvenile herring face a whole new set of predators such as rockfish, murres, and other seabirds (many of which are nesting in May). As they mature, the herring will provide food for many larger animals such as sea lions, harbor seals, and dolphins. Juvenile anchovies appear in Elkhorn Slough while adults spawn in San Francisco Bay Juvenile anchovies appear in Elkhorn Slough In April or May, tiny young anchovies first begin to appear in estuaries such as Elkhorn Slough. These young anchovies developed from eggs that were released by their parents between January and March. Surprisingly, adult anchovies are almost never found in Elkhorn Slough. Thus, it's not clear how the young anchovies get into the slough each spring. One possibility is that adult anchovies release their eggs or larvae just outside the mouth of the slough at low tide. Incoming tidal currents might carry these fertilized eggs into the slough. During periods of extreme tides (full or new moon), the anchovy eggs could be carried all the way from the ocean to the warmer, shallow waters of the upper slough. One way or the other, by May the slough contains an abundance of tiny young anchovies—more than at any time of year. At high tide, schools of juvenile anchovies gather in the Slough's small creeks and flooded salt marshes. They mostly eat copepods, which are abundant in the Slough in spring. Instead of leaving the slough in May, as the herring do, the young anchovies will remain in the slough through the end of summer. Adult anchovies spawn in San Francisco Bay In San Francisco Bay, anchovies seem to operate on a later time schedule than those in Elkhorn Slough. Adult anchovies gather just outside the Golden gate in February and March. They migrate into the Bay in April, then release their eggs in May and June. Thus, unlike Elkhorn Slough, San Francisco Bay hosts large populations of adult anchovies. Each May, these anchovies release millions of eggs. In July or August, the adult anchovies will migrate out of San Francisco Bay and into the Gulf of the Farallones. There they will continue spawning into October. At this time of year, the water in the Gulf of the Farallones has typically begun to warm up a bit due to reduced upwelling, which may help the anchovy larvae develop more rapidly. Note: In the Pacific Northwest, a northern subpopulation of anchovies spawns from mid-June to mid-August. Adult anchovies are typically found along the Oregon and Washington coast only from May to October. They are particularly abundant in the Columbia River plume, as was in and around estuaries such as the Columbia River Estuary, Grays Harbor, and Willapa Bay. Staghorn sculpin leave estuaries Like herring, staghorn sculpin (Leptocottus armatus) begin to leave the creeks of Elkhorn Slough in May. However, the juvenile sculpin don't head out to sea in May, but gradually migrate downstream, toward the mouth of the slough. During June and July, most of these sculpin will leave the slough to make homes for themselves on the seafloor of Monterey Bay. Others will spend their entire lives within the estuary. Shiner perch enter estuaries to spawn Just as many young fish are leaving the shallow nursery-grounds of the slough in May, adult shiner perch (Cymatogaster aggregata) are entering the slough to give mate and birth in the shallow tidal creeks that feed into the slough. The females enter first, in late April, followed by the males. The males fertilize eggs, which develop inside the female's body. In late May, the female perch give birth to live young in the warm, shallow marshes of the upper slough. Then both males and females head back out to sea. The young shiner perch develop rapidly, eating the multitudes of tiny copepods and amphipods that live on the bottom of the slough. They also eat creek and slough vegetation. Like the anchovies and sculpin, the juvenile perch will leave the slough by the end of summer. In the mean time, they provide essential food for nesting Caspian terns and newly weaned harbor seal pups. Leopard sharks give birth  Leopard shark at the Monterey Bay Aquarium (Source: Chad King / SIMoN NOAA ) Some leopard sharks (Triakis semifasciata) live in the slough all year round, where they are by far the most common elasmobranch. In early spring, hundreds of female sharks migrate from the Central Coast waters and gather inside the slough, where they give birth in April or May. Note: In addition to congregating and giving birth in coastal estuaries, leopard sharks may gather in warm, sheltered coastal areas with shallow, sandy bottom. One such spot is the "Shark's Cove" surfing spot about a mile west of Capitola (in the heart of the Monterey Bay "upwelling shadow"). After carrying their developing young inside their bodies for almost a year, the female leopard sharks give birth in the warm shallows of the slough. When giving birth, they contort their bodies and squeeze out up to three dozen baby leopard sharks, each about eight inches long. Soon after the female leopard sharks give birth, they mate with male sharks, which gather in the slough in April and May. Some of the sharks will stay in the slough all year long, but others will leave in July or August. Although leopard sharks can grow to over six feet long, they are no danger to people. They spend most of their time swimming just above the seafloor, hunting crabs and small fish. They can also extract deep-digging clams and fat innkeeper worms from their burrows, though scientists aren't exactly sure how they manage this. Bat rays enter estuaries  A bat ray swimming just above the seafloor. (Source: NOAA Fisheries) At the same time as leopard sharks are making their way into the slough in spring, so are flocks of bat rays (Myliobatis californica). Their three- to six-foot wings flapping slowly, the bat rays converge on the slough and head for the shallow mud flats, following the rising tide. Like the leopard sharks that arrive in spring, the female bat rays are pregnant, and have been carrying their young inside their bodies for almost a year. In a convenient nursery time-sharing arrangement, bat rays typically give birth June, about a month or two after the leopard sharks. After giving birth, the bat rays will stay in the slough until October, when they will head out to forage on the seafloor of the nearby continental shelf. Aside from giving birth, bat rays spend their time in the slough gliding slowly just over the surface of the mud, seeking buried clams and worms. When a bat ray finds a clam or worm near the surface, it flaps its wings to stir up the sand and mud and expose its prey. In a single night of intensive foraging, a bat ray can dig channels in the bottom of the slough that are three feed wide, 15 feet long, and 20 inches deep. When hunting a fat innkeeper worm or other deeply buried prey, the bat ray presses its wing flat over the animal's burrow, then lifts the wing suddenly like a toilet plunger, sucking out the hapless animal. If the animal is a worm, the bat ray seizes the worm in its mouth and gradually draws it inside like a piece of oversized spaghetti. Shovelnosed guitarfish enter estuaries Along with leopard sharks and bat rays, shovelnosed guitarfish are a third type of cartilaginous animal that enters the slough in May. The Central Coast is at the northern end of the range for guitarfish, and adult females probably give birth in May in Southern California. However, juvenile guitarfish begin to enter the slough in May. As the summer progresses, adult guitarfish will gradually make their way up the California coast to feed in the slough, reaching maximum numbers in August. While in the slough, they eat mostly green crabs (Hemigrapsus oregensus), which are the most abundant type of crab in the slough. They also snack on a few juvenile flatfish that have lingered too long in their nursery/feeding areas. The guitar fish typically leave the slough in October or November. Conveniently this is just before another elasmobranch, the gray smoothhound, enters the slough to feed on green crabs. Wetland and shore birds brood eggs As described in the May seabirds page, several types of birds build nests in and around coastal wetlands during May. These include Brandt's cormorants and Western Gulls, which nest on abandoned piers and navigation markers. Pelagic cormorants often nest in tall trees, such as eucalyptus, that grow near productive wetland areas. Forester's terns and Caspian terns build nests directly on the ground, on sandbars, islands, and abandoned dikes. |