|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

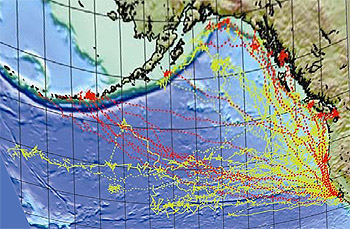

Heading home from the party: The first gray whales migrate north  A gray whale, showing the typical crop of large barnacles on its back. (Source: NOAA) Since blue whales and humpback whales are rare on the Central Coast in March, the largest marine mammals you are likely to see at this time of year are gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). March and April are the peak months for gray whales to migrate northward along the Central Coast from their winter breeding areas in Baja California to their summer feeding grounds near the Bering Sea. At the same time, a few gray whales are already migrating northward from Baja California at this time of year. At 35-50 feet long, gray whales are somewhat smaller than the blue and humpback whales that frequent Central Coast coast waters during summer and fall. Adult gray whales have mottled gray and black bodies that are typically encrusted with light-colored barnacles. Because they often hug the coast, migrating gray whales are particularly easy to see from shore. The best places to watch for migrating whales are high sea cliffs and headlands along exposed coastal areas and points of land, such as those northwest of Santa Cruz and south of Monterey. The best time to watch for migrating whales is in the in the morning, when the sea surface is relatively calm and the fountains of spray from their exhaled breaths are relatively easy to see. The gray whales swimming north along the Central Coast in late February and early March are just the first of several thousand that will pass by over the next few months. Most of the early migrators are newly pregnant females who spent the winter socializing and mating in one or two sheltered lagoons along the Baja coast, like college students on spring break. By March, these female whales are more than ready to finish their 7,000 mile trek back to Alaska. It's not an easy trip--every year some whales die during their migration due to starvation, disease, orca attacks, and ship collisions (in many areas, the shipping lanes coincide with the whale migration routes). Once they get back to the Bering Sea, the whales will spend their summer feeding on small, shrimp-like creatures that live in sea-floor mud. Scientists have long believed that gray whales ate little or nothing during their eight-month migration and winter vacation. Thus, it was assumed that the early-migrating pregnant females were hurrying north because they were hungry. However, recent studies suggest that at least some gray whales stop for a day or two to feed at food-rich areas along the central coast, including Monterey Bay, the Farallon Islands, and the mouths of San Francisco, Tomales, and Drakes Bays. In these areas, gray whales have been observed eating young krill rather then their usual bottom-dwelling prey.  A gray whale exhaling as it swims along the sea surface. (Source: Steven Swartz / NOAA/NMFS) Looking out from shore, you can tell whether a gray whale is migrating or feeding by watching the way it dives. A migrating gray whale typically makes two or three short dives of about 15 seconds each, followed by a deeper dive of up to five or six minutes. During this migratory dive sequence, the whale may travel about half a mile, mostly underwater. In contrast, a feeding gray whale makes repeated short dives of less than a minute each, often swimming in circles and doubling back on its path instead of moving along the coast. Although pregnant female gray whales lead the northward migration, the adult males are close behind, and typically pass along the Central Coast in late March. Young, immature whales (ten-ton "yearlings") come next, in April and May, followed by; nursing females and newborn calves in May or June. Winter dolphins leave as summer dolphins arrive Dolphins and porpoises perform a "changing of the guard" in March, with some species leaving just as others are arriving. For example, pods of white-sided dolphins, which you may see occasionally during the winter months, leave the area at this time of year, perhaps heading south to give birth. Similarly, many Risso's dolphins and long-beaked common dolphins leave Monterey Bay in March, heading toward Southern California (though a few may stick around all year). Thus, you are less likely to see large pods of these dolphins on the Central Coast during the spring and summer. As the dolphins are leaving, Dall's porpoise and harbor porpoise begin to arrive in Central Coast waters. These porpoise prefer cold water and usually show up right at the beginning of upwelling. Some Dall's porpoise may migrate northward to the Central Coast from Southern California at this time of year. Throughout the spring, you can see these fast-moving porpoises chasing market squid and small fish, their sudden bursts of speed leaving trails of spray across the sea surface. The Dall's porpoise and harbor porpoise usually leave the area when upwelling tapers off in July or August (just as pods of dolphins start to return with the warm water of fall). Male sea lions head south to breed In late February or March, adult California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) begin to leave the Central and Northern California Coast and head south to their breeding areas on the Channel Islands and along the coast of Baja California. Sometimes groups of these adult males will stop briefly along the Central Coast to feed, but like the orcas, they don't stay long. At their southern rookeries, the male sea lions will spend the summer meeting, competing for, and mating with adult female sea lions, most of whom spend the entire year down south. Soon after the big guys leave the Central Coast, gaggles of juvenile and yearling sea lions begin to arrive in the area after leaving their Southern California pupping grounds. These rowdy groups typically include many young pups, as well as a few older juveniles who guard the pack and keep the youngsters in line. I discuss these incoming groups of rowdy youngsters in greater detail in April. .Adult elephant seals leave the area  This map shows paths taken by elephant seals across the North Pacific after they leave Ano Nuevo Island. Red dots indicate male seals; yellow dots indicate females. (Source: Dan Costa / SIMON) Their mating and pupping completed, most adult elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) also leave the Central Coast in March. The males leave shortly after mating, in late February, and swim directly to their preferred feeding areas in the Gulf of Alaska, and as far north as the Aleutian Islands. The female elephant seals leave as soon as they have weaned their pups. Most elephant-seal pups are born in January and February, and nurse almost continuously for the next four weeks. After about a month, however, the mothers refuse to feed their young, and head off to find food for themselves. At this point, the female elephant seals have had no food since they came ashore to give birth in December. By the time they finish nursing, these dedicated mothers will have lost about one third of their body weight. So they head out to the open waters of the North Pacific to forage for about two months. They will return to the Central Coast in May to come ashore once more to moult. Because they make two round trips from their California haul-out areas to their northern Pacific feeding areas each year, some elephant seals may travel up to 23,000 miles in a year, farther than any other mammal, except perhaps some blue whales. Truly animals of the open ocean, foraging elephant seals spend more time underwater than at the sea surface, diving as deep as 5,000 feet and staying down for 20 minutes at a time. They spend this time in the dark depths chasing deep-water squid and bottom dwelling sharks and rays, hagfish, ratfish, hake, rockfish, and octopus. Note: During warm-water years, female elephant seals' post-nursing foraging trips lasted about several weeks longer than during cold-water years, presumably because food was harder to find. But even with these longer trips, females gained less weight than during normal years. Harbor seals gather before giving birth Harbor seals, unlike most of the other marine mammals on the Central Coast, are "homebodies." Each harbor seal spends most of the year (and most of its life) in its own, relatively small "territory" (though only the males are territorial). However, in March, pregnant female harbor seals leave their kelp beds to gather on a few secluded beaches, where they will give birth in April. Fur seals leave the area Though not as numerous or obvious as California sea lions, a few Northern fur seals spend their winters on the Central Coast, particularly around rocky areas such as Big Sur, Ano Nuevo, and the Seal Rocks, near San Francisco, as well as at the Farallon Islands. In March or April, however, these fur seals leave the area and head out to feed in the open waters of the North Pacific. Female sea otters teach their young to forage  Sea otter mother and pup sleeping in the kelp beds. (Source: (c) Kim Fulton-Bennett) Sea otters mate and give birth all year long, but the majority of pups are born in mid-winter, from November to January. As befits a creature born in the middle of the storm season, baby sea otters are born with a "life vest" of thick fuzzy fur. Although this fur won't let them sink, it also won't let them dive for food, so they are completely dependent on their mothers for food and protection. By March, some of the year's crop of young otters are already getting too large to nurse (though that doesn't stop them from trying). They have also shed their furry "life vests" for the sleeker coat that will let them dive beneath the waves for food. At this point, you can often see mother sea otters teaching their young how to hunt for food in the kelp beds. March may be a relatively easy time for the young otters to find food because the understory algae is thin, leaving the otters' crustacean and molluscan prey fewer places to hide. Adult otters often specialize in catching certain types of prey, such as clams or sea urchins. Thus, part of what a mother otter has to do is to teach her youngster the skills needed to catch and eat prey in the area where they live. Only after the basic hunting skills are honed does the mother show her offspring how to use tools, such as rocks, to open the prey they have caught. In early spring, groups of adults and baby sea otters can often be seen lounging and feeding in areas where the kelp canopy has survived the winter and is still relatively thick or extensive. Field observation: Cooperative baby sitting in sea otters One spring afternoon I stood on the bluffs near Lighthouse Point in Santa Cruz and watched a group of five or six female otters and their young. The adults were snoozing on their backs around the edges of a small circle of open water surrounded by dense kelp. Several young otters floated close by, wrapped in kelp blades, apparently sleeping. But one little otter apparently couldn't sleep, and was busy swimming back and forth in the open water between the adults. The youngster tried to climb onto its mother's belly, but she gently pushed him off and rolled over, apparently trying to resume her nap. The restless young otter then dove underwater for about 10 seconds and came up directly underneath another adult, who promptly rolled over and brusquely pushed the youngster away. Obviously looking for trouble, the young otter then swam over to a third adult otter and pulled or nibbled on his back leg, but was rebuffed once again. The young otter then practiced diving a few times, always coming up to the surface within the circle of adults. Eventually one of the adult otters lazily rolled over and dove beneath the surface, emerging outside the circle a few minutes later with a small clam in his paws. The young otter then left the circle and started to approach the adult. After swimming a few yards, however, the youngster changed its mind and returned to the "nursery," where it snuggled up next to its mother and eventually fell asleep. A little later that year, on a day when the ocean was very calm, I watched a mother otter foraging with her somewhat older pup right in the shallow water right at the base of the cliffs. Occasionally the young otter would dive and swim around, but it usually emerged empty handed and then floated on the surface, waiting for it's mother to bring it a tidbit. Sometimes the mother would dive and bring up a clam or mussel and offer it to the baby, who would gnaw at it in a futile attempt to open it and get into the meat inside. Several times, in his clumsy efforts to get a shell open, the baby dropped the food right into the water, then dove down to look for it as it sank. I suppose this provided an exercise in finding prey that was not attached. Other times, the mother would partially open the morsel and then swim over and hand it to the youngster to finish off. Sometimes the baby would get impatient and swim over to the mother to beg food from her. If she wanted to get any food for herself, the mother otter had to surface far enough from her pup to eat the item before the pup arrived to beg or grab it from her. This little game got even more complicated when a gull flew over to try and snatch food right out of the young otter's paws. |